Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s ruling coalition suffered stinging electoral defeats in two key economic powerhouses, piling pressure on Germany’s fractious government.

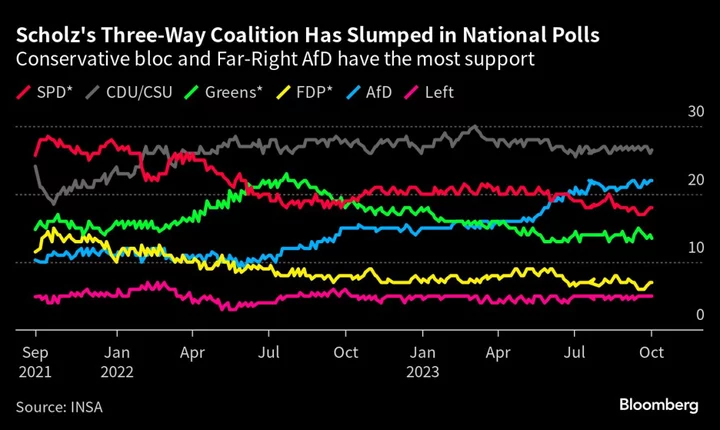

As voter frustration deepens, all three governing parties lost support in Bavaria and Hesse, while the far-right Alternative for Germany — known as the AfD — emerged as the second-strongest force in both states, underlining its growing national presence.

Scholz’s three-way alliance has been beset by infighting, while voter concerns intensify over Germany’s economic malaise, illegal migration and the war in Ukraine. The Social Democrats, the Greens and the Free Democrats lost a combined 12.5 percentage points in Hesse and 6.9 percentage points in Bavaria, according to projections from public broadcaster ARD.

“When all coalition parties lose in both states, there’s a message here for Berlin,” SPD General Secretary Kevin Kuehnert said in interview with ARD.

In Hesse — the home of the Frankfurt financial hub — the SPD slumped into third place after a campaign led by Nancy Faeser — the federal interior minister — bringing the defeat closer to Scholz.

“The election result is very disappointing,” she said in a TV interview. “Unfortunately, we were unable to break through with our topics,” such as free daycare for all kids.

Germany’s conservative bloc retained control of both states, ensuring political continuity. The Christian Democratic Union won 34.3% of the vote in Hesse, while its Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union, took 36.7%. The allies in Berlin make up the largest opposition group at the national level.

In Bavaria, the anti-immigrant AfD was the biggest gainer, while the Social Democrats slumped to fourth. The FDP dropped out of the regional parliaments both states, potentially prompting the pro-business party to oppose its left-leaning governing allies even more.

Scholz has dismissed the AfD as a “demolition squad” that exploits the fears of ordinary citizens, but his administration has struggled to convince voters that Germany’s transition to a cleaner and more technologically advanced economy is worth the risk.

After distributing billions of euros in aid to soften the impact of the pandemic and the energy crisis, the chancellor has ruled out a stimulus program, even after Europe’s largest economy barely emerged from a winter recession in the second quarter.

An influx of refugees as well as illegal migrants has added to the coalition’s headwinds, with the parties struggling to come up with convincing policies to ease concerns and leaving them open to attack from the AfD and the conservative bloc.

In a poll for ARD published in late September, 67% of respondents said that the admission of immigrants was currently either “rather not” or “definitely not” manageable. Almost half of the 1,326 people polled said they were concerned that too many foreigners are coming.

Lifted by war refugees from Ukraine, the number of immigrants into Germany reached 2.7 million people last year, according to the German statistics office, which marked a new record exceeding figures from the Syrian refugee crisis.

The run-up to the Bavaria vote was overshadowed by an antisemitism scandal around the CSU’s coalition partner, the Free Voters. The regional party’s leader Hubert Aiwanger was under fire over links to a flier from the 1980s that threatened traitors to the “fatherland” with a “free flight up the chimney at Auschwitz,” the Nazi death camp.

While acknowledging the flier’s existence, Aiwanger said he wasn’t the author, and Premier Markus Soeder from the CSU decided there were insufficient grounds to dismiss Aiwanger.

Soeder’s messy handling of the scandal ended up hurting the CSU, which stumbled to its worst result in Bavaria since 1950. Support for the Free Voters rose, and the two parties will likely continue their alliance in Bavaria.

--With assistance from Christoph Rauwald.