Political leaders in Southeast Asia‘s biggest Muslim-majority nations got a reminder from Malaysia last week that the battle for the hearts and minds of voters is shifting, and religious conservatism is gaining ground.

In provincial elections last weekend in Malaysia, far-right Islamist groups strengthened their hold on three of six states up for grabs. While Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s multi-cultural coalition retained the three states it controlled previously, it saw Islamists wrest more seats away in Selangor, the wealthiest state still under its rule.

The results reflect a political reality gripping a region that’s seen decades of income growth checked by the pandemic and a global economic slowdown. In neighboring Indonesia, President Joko Widodo’s government has had to make political concessions to religious conservatives with growing clout in the world’s most populous Muslim nation.

In July, Indonesia’s Supreme Court effectively ended state recognition of inter-faith marriages amid pressure from conservatives. Last December, the country also passed a sweeping law that among others criminalized people who have sex outside marriage in what was the biggest showing of conservatives’ power in influencing state policies. Jokowi, as the president is known, in 2019 made a top Islamic cleric his vice president, alarming progressives about the impact on policy.

“In my opinion, we complement each other: Nationalist, religious. Our target is all Indonesian citizens,” Jokowi had said when announcing his running mate.

Anwar and Jokowi face a growing dilemma: the rise of conservative politics increases pressure on their governments to burnish their religious credentials at the cost of economic policies that spur business and investment.

Prior to the Aug. 12 state elections, Anwar’s government canceled a music festival because members of British band 1975 shared a same-sex kiss on stage. Malaysia also made owning one of Swatch Group’s rainbow watches punishable by up to three years in prison, because of their pride theme.

Gaming and alcohol stocks slumped in Malaysia last November after unexpected electoral gains made by the Malaysian Islamic Party, or PAS, which champions a theocratic state and is the biggest party in the Perikatan Nasional, a bloc of conservative parties led by former premier Muhyiddin Yassin. In Bali, officials sought to distance themselves from a sweeping sex law that could hurt the island’s tourist-reliant economy just as pandemic restrictions eased and international travel picked up.

Fully carrying out religious conservatives’ agendas poses economic risks for nations seeking to boost foreign direct investment, “especially with investors increasingly focused on ESG issues,” said Peter Mumford, who oversees the Eurasia Group’s coverage of Southeast Asia.

“Draconian social policies, such as those announced in Indonesia recently, risk undermining the appeal of countries for FDI,” he said. “Companies selling into and producing in these countries need to be conscious of the social trends as they affect consumer behavior as well as in some cases regulatory requirements.”

In Malaysia, the trend toward conservatism is being driven by young voters like 22-year-old Firdaus Mohd Din, who are sold on the idea of faith-based politics. Firdaus remembers being impressed by a television broadcast of Anwar’s rival, then-premier Muhyiddin, lifting his hands in prayer for God’s protection at the height of Covid-19.

“Muhyiddin’s the better person to lead the country — he gave us aid during the pandemic and I believe he’s more Islamic than others,” said Firdaus, a food delivery driver in Selangor state.

Although Muhyiddin lost to Anwar in the national elections, he is counting on Malay voters like Firdaus, who are Muslims by law, to eventually return to power. The widening influence of these conservative groups’ on young voters can pressure Anwar to adjust policies aimed at winning them over.

“This happens even in Europe and America where the far right have been making progress in politics,” Anwar said on Thursday in reference to religious conservatives. “It is our job to convince them we are sincere.”

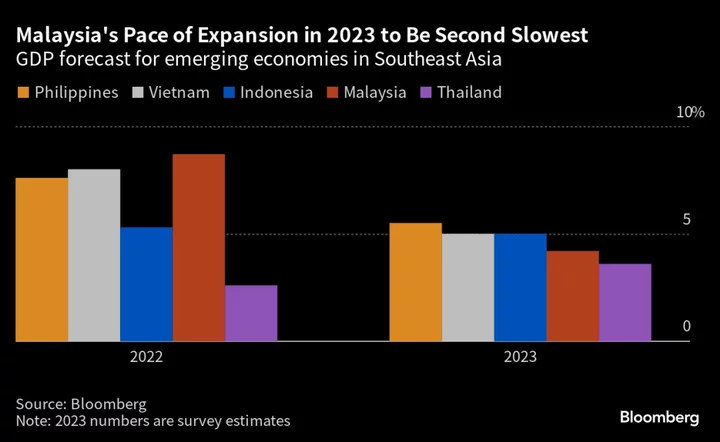

Such changes in Malaysia will be closely tracked by investors and rating agencies to see if it affects investment inflows into the region’s wealthiest emerging economy as it stages a recovery from the pandemic-induced downturn.

With anxiety over economic issues running deep, “young voters here seem to have found spiritual solace with the right-wing parties and have bought into their communal rhetoric,” said Ibrahim Suffian, director at pollster Merdeka Center which correctly predicted the elections outcome.

Economic turmoil and frustrations built up during coronavirus lockdowns — where gig economy workers like Firdaus in Malaysia were among the hardest hit — have given political Islam fresh momentum with its emphasis on community and shared purpose.

Repeated crises are leaving young people struggling to embrace “the ambiguity and complexity of the modern world,” said Noor Huda Ismail, a security expert at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. “Conservatism — especially in religion — can provide that stability by saying if you follow religion seriously, your life will be easier,” he said.

Part of this has to do with religious education, which starts early in Indonesia and Malaysia. PAS founded and ran Islamic preschools as early as the 1980s in Kedah and Terengganu, where the Islamist party trumped on Saturday. Today it operates 2,497 preschools across Malaysia, with 125,065 students aged four to six years old enrolled as of 2022, according to the party.

Malaysia’s plethora of state, private and international religious schools increased religious conservatism among Malays, according to Dina Zaman, co-founder of think tank IMAN Research in Malaysia. “This phenomenon came about from the distress of parents who feel that our local education system is failing their children,” she said, adding that improving national schools could address that.

The issue is not Islam itself, but the misuse of religion as a political tool to paint opponents as “enemies of Islam” at the expense of policy ideas and nation-building, according to Khalid Samad, communications director of the National Trust Party, an off-shoot of PAS aligned to Anwar.

Still, it’s a challenge to counter PAS’s “very simple, 15th century messaging” that Islam is under siege and elections are a battle for Muslims to fight back, Khalid said.

Leaders of Malaysia and Indonesia have issued warnings against letting religious-focused political parties gain too much power. Indonesia’s president has regularly railed against “identity politics.” Malaysia’s leader, Anwar gave authorities the greenlight to arrest individuals who use religion and race to sow dissent.

“I am not against Islamic ideals, I’m not against even Islam in politics,” he said in an interview in January soon after becoming premier. “But I reject this notion of using religion” in order to “fortify your strength and abuse that position.”

--With assistance from Ravil Shirodkar, Kok Leong Chan and Sanjit Das.