Two days after the European Union declared it will push for a global phase-out of most fossil fuels well before 2050, Shell Plc signed a 27-year agreement to buy Qatari liquefied natural gas for the Netherlands.

It’s not the first multi-decade deal to tie the bloc to dirty fuels beyond its targeted deadline — just last week France’s TotalEnergies SE signed a similar contract. The agreements highlight the challenge in reconciling the EU’s ambition to reach climate neutrality by 2050 with its need to ensure energy security after last year’s historic crisis.

“Energy companies seem to be betting Europe will need more gas than politicians predict,” said Christian Egenhofer, senior researcher at the Centre for European Policy Studies.

While Europe has made strides in replacing the cheap Russian gas imports that used to power its economy — mostly by buying liquefied versions of the fuel from places like the US or Qatar — jump-starting its transition to cleaner alternatives has proved difficult.

Governments across the region have prioritized expanding renewables after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine underscored Europe’s need for independent sources of energy, which also cause less damage to the environment.

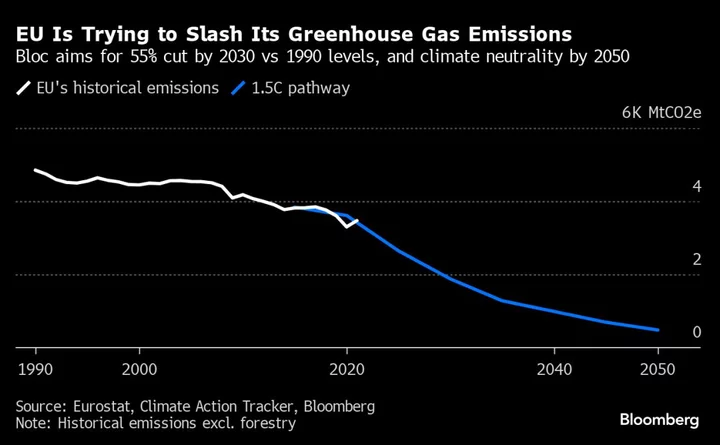

But high borrowing costs and uncertainty about the commercial viability of some technologies have stalled investments and raised questions about the reachability of Europe’s climate goals. The EU has a binding aim to cut greenhouse gases by at least 55% by 2030 from 1990 levels, and produce no net emissions by the middle of the century.

On Monday, the EU endorsed the global phase out of “unabated” fossil fuels, meaning that countries could only burn coal, gas and oil if they use technology to remove the resulting emissions, such as carbon capture and storage. Such methods are currently limited in scale. The condition will form part of its negotiating mandate at this year’s United Nations COP28 climate summit in Dubai.

“Long-term gas supply contracts between producers and market participants do not lock the EU into a natural gas dependence, since they do not necessarily commit the EU to consume it domestically,” said EU energy and climate spokesman Tim McPhie.

Under the two deals signed with Shell, starting in 2026, QatarEnergy will deliver as much as 3.5 million tons of LNG a year to Rotterdam’s Gate import terminal for 27 years. The same amount will flow to France, which made a U-turn on long-term LNG deals last year, when it revived a supply accord with a US producer which it had axed in 2020.

While there are currently no legal limits for private companies to sign long-term agreements, some EU diplomats are concerned that the deals show top buyers see a bright future for gas despite the bloc’s bets on renewables. Other observers say it’s a risk for the companies involved if the transition to cleaner energy proves successful.

“Private investments into fossil gas deliveries beyond mid-century are at risk of becoming stranded,” said Matthias Buck, Director Europe at Agora Energiewende. “Particularly, as there are many questions around the future availability and costs of carbon capture and storage.”

Qatar, meanwhile, is rushing to find customers and leveraging growing fears over energy security to nail down more long-term deals. It has invested tens of billions of dollars to increase output 64% by 2027. While European companies were initially reluctant to sign long-term deals, Shell has bought shares in key Qatari LNG projects, and Italy’s Eni SpA is also a stakeholder. The latter has yet to announce a similar deal.

It’s possible the companies have got the agreements over the line just in time, as the EU is seeking to ban deals for supply of unabated fossil fuels that last beyond 2049. The draft law is being negotiated by member states and the European Parliament, with a decision on its final shape expected before the end of this year.

Other European energy companies rule out locking in such long deals in light of the region’s climate goals. Germany’s Uniper is not prepared to conclude supply contracts running until 2050, according to a spokesperson.

EU policymakers acknowledge that some energy-intensive industries will need fossil fuels for longer and will have to rely on emissions-removal technologies, but stress those should not be used to delay climate action in sectors where effective alternatives are available.

There are signs that European buyers are starting to embrace such alternatives, according to Woodside Energy Group Ltd Chief Executive Officer Meg O’Neill. She said that while long-term gas contracts are still in play, “no one is saying they are not interested in other fuels in the future,” with buyers also asking for hydrogen, ammonia and carbon capture and storage.

Still, the immediate need to secure energy supplies leaves buyers with limited room for maneuver as renewables aren’t yet able to fill the gap, according to Peter Clarke, senior vice president of global LNG at ExxonMobil Corp.

“One lesson I hope we have learned from the current geopolitical crisis is that having adequate energy supply and security to meet supply needs is crucial,” he told the Energy Intelligence Forum in London on Wednesday. “We can’t predict the future, but we can certainly prepare for challenging times.”

--With assistance from Anna Shiryaevskaya, Priscila Azevedo Rocha, Ania Nussbaum, Petra Sorge and John Ainger.