European central bankers’ price stability mission is on a collision course with the goal of combating climate change, unless they change their ways.

The transition to a lower-carbon economy may fuel inflation — but raising interest rates in response to that could hinder investment in cleaner energy. So monetary policy and efforts to save the planet risk working against each other, casting a shadow over the prevailing consumer-price-targeting philosophy of the past three decades.

That augurs tough choices for the European Central Bank. Raising borrowing costs means lifting the price of investment in combating climate change. But if officials tolerate higher consumer prices instead — an approach aired during the ECB’s 2021 strategy review — they risk failing to fulfill their mandate.

More radically, policymakers could try to square the circle by revamping monetary frameworks to incorporate an until-now unpalatable pipe-dream of the region’s environmental activists that is already embraced in Asia — green lending.

Climate emergencies such as the Canada wildfires and southern Europe’s drought underscore the problem, and however central bankers respond, their arms-length approach to aiding the transition is getting harder to sustain. With the European Union committed to establish the world’s first climate-neutral continent by 2050, the region is at the vanguard of confronting the problem.

“If they disincentivize investments, it could be counterproductive for the energy transition,” said Didier Borowski, head of macro policy research at Amundi, which manages $2 trillion as Europe’s biggest asset manager. “There is a complex trade-off between their actions and their mandate of price stability.”

The urgency of action is getting clearer by the day as the planet continues to experience worrying extremes, from record-low Arctic ice levels to record-high ocean temperatures.

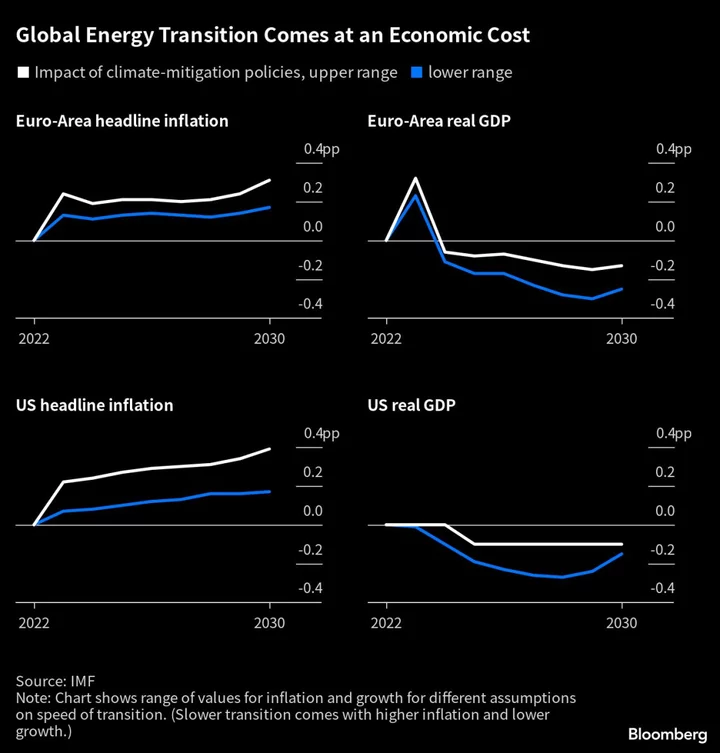

The transition is likely to boost inflation because of impacts ranging from more carbon taxes to how high-emission workhorse technologies get replaced by initially more expensive but greener alternatives.

BNEF Theme: Pathways to Net Zero by 2050

Related spending reached a record $1.1 trillion last year, according to Bloomberg NEF, which reckons annual global investments of about $6.7 trillion will be needed to reach net zero by 2050. Central banks impact that because debt costs affect renewable projects more than fossil fuels, said analyst Stephanie Muro.

Demand for metals enabling the shift from hydrocarbons is set to soar from 52 megatons today to 242 megatons in 2050. Appetite for lithium, a central component of batteries, is likely to outrun supply.

Euro-area inflation may be as much as 0.3 percentage point higher through the end of the decade, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Similarly, Sweden’s Riksbank found that energy prices will increase during the transition as phasing out carbon-intense technologies squeezes aggregate supply, and investment in new ones bolsters demand.

“According to our analyses, the energy transition implies moderately higher inflationary pressures” said Bundesbank official Sabine Mauderer, the vice chair of the Network for Greening the Financial System who will soon lead that group of monetary and supervision authorities. “Central bankers must consider this development. At the same time, price stability is the best contribution we can make to ensure the transition will be successful.”

Climate change itself is stoking prices as shifting weather patterns undermine natural systems that modern economies are built on, from droughts ravaging agriculture to supply disruptions caused by rivers running dry.

Natural disasters will have “significant positive effects” on inflation, making the ECB’s job increasingly difficult, economists at SOAS in London wrote in 2021.

“Inflation at the moment is already driven by climate change in a way that I find personally very frightening,” said Jens van ‘t Klooster, an assistant professor at the University of Amsterdam.

While central banks have embraced a role in fighting climate change, many including the ECB cite their inflation mandates as a brake to that.

But Borowski at Amundi says that while it’s clear the job of policymakers to anchor inflation expectations, monetary regimes might need to adapt and be ready to permit some price growth stemming from the transition.

“Central bankers cannot just say, ‘well, this process is inflationary in the short run, I will hike rates,’” he said, describing that response as “counterproductive.”

The ECB has claimed the impact of an orderly transition on its policies should be limited, while suggesting some coping strategies. They include emphasizing inflation gauges excluding energy, and targeting a longer time horizon.

That could mean a divergence lasting two decades, exceeding the terms of two ECB presidents.

Former IMF Chief Economist Olivier Blanchard argues that such a time period is still finite. An advocate of raising inflation targets, he reckons the climate-change shift doesn’t justify such changes.

“This is just a transition issue,” he said. “If we are thinking of higher green investment as a 10-year, 20-year project, this transition issue is minor.”

While the ECB has proved open to evolving, and promises another strategy review in 2025, officials are nervous about diverging from their mandate, not least at a time of high inflation. For ECB Executive Board member Isabel Schnabel, nothing should be allowed to supersede its core mission.

“Our best contribution to fostering investment — in the green transition but also in other areas — is to get back to price stability and create, as far as we can, a stable macroeconomic environment,” she told Bloomberg this year.

Guntram Wolff, who leads the German Council on Foreign Relations and regularly advises European governments, agrees.

“It’s the job of finance ministries, taxpayers and politicians to cushion the costs and effects of climate change,” he said. “It’s not the job of a central bank to accept higher inflation and involve certain parts of society more closely into stemming the costs.”

The political tensions are evident. The Swiss National Bank, which is reluctant to embrace a role in the transition, faced protests at its shareholder meeting in April.

ECB President Christine Lagarde has sought to prioritize the issue, and could be uncomfortable that delivering price stability might hurt transition investment.

That’s why green lending might be a solution. Favored by activists but resisted by officials reluctant to subsidize any individual sector of the economy, the policy might actually be self-serving to help support their core task.

The NGFS has also looked at targeted credit operations as one tool central banks could consider.

Similar to past ECB offerings that gave banks an interest-rate discount if they used funds to extend credit, such a measure could provide new loans costing less if deployed to fight climate change.

“The idea shouldn’t be that central banks go off by themselves making all this climate policy because elected officials aren’t doing things,” said Klooster, a key proponent of the tool. “But maybe stopping some investments that aren’t really aligned with the transition, or maybe promoting some investment that for some reason aren’t made, should be OK.”

Asian central banks have used such instruments for a while to support the transition.

The People’s Bank of China has offered cheap funding to banks which lend to firms that are helping reduce carbon emissions since November 2021. The same year, the Bank of Japan introduced its own lending scheme.

Lagarde has signaled openness to the idea. Schnabel has also cited it for when there’s room to ease policy again. Neither have linked it with inflation targeting.

European state-backed lenders could do the job. But green lending also falls within a central bank’s price-stability mission, since more renewable energy will have a “significant dampening effect on inflation,” said John Beirne, vice chair of research at the Asian Development Bank Institute and a former ECB economist.

“I don’t think there should be major concerns around explaining why these types of programs would be taking place within the overall context of the central-bank mandate,” he said.

Policymakers have been slow to agree with that, having long argued that it’s the government’s task to decide which industries to support. But former Bank of England chief Mark Carney insists that attitude needs to shift.

“Climate change is macro critical,” he said in a recent speech. “Climate policy and the pace of the transition directly impact the efficacy of fiscal and monetary policies.”