US military officials are so concerned about the quality of generic drugs that the Department of Defense is devising a program to test the safety of widely used medicines.

Defense officials are in talks with Valisure, an independent lab, to test the quality and safety of generic drugs it purchases for millions of military members and their families, according to several people familiar with the matter who asked not to be named as the details aren’t public.

The move raises questions about the Food and Drug Administration’s ability to adequately police generic medicines. With mounting drug shortages, most of which are caused by quality problems, military officials have gone so far as to call vulnerabilities in the drug supply chain a national security threat.

The FDA is responsible for ensuring that America’s drugs are safe, but it’s gotten harder for the agency to police quality because generic drugmakers have shifted operations to India and China where costs are lower and the US has little oversight. The Pentagon’s proposed program isn’t currently targeting the expensive, brand-name drugs advertised on TV, but rather the older copycat drugs that make up more than 9 out of 10 prescription medications that Americans take.

Aware of growing quality problems, the White House has convened a task force that’s exploring whether testing could be expanded more broadly in the US. If the Pentagon pilot is successful, it could serve as a model for Medicare or the Department of Veterans Affairs, people familiar with the matter said. But there are tensions in Washington: In conversations with the White House, the FDA has pushed back against additional quality checks, questioning the accuracy of third-party labs like Valisure.

The agency said it stands behind medicines sold in the US and Americans can be confident about their quality.

Generics 101

Drugmakers are required to test their drugs for impurities. The industry doesn’t share results with the FDA, rather companies keep files that agency inspectors comb through when they visit drug production plants once every year or two. Over the last decade, FDA inspectors have found many manipulated test results. The agency can ask a plant to shut down if it finds major problems. This can lead to or exacerbate drug shortages, which is an acute problem in the US right now.

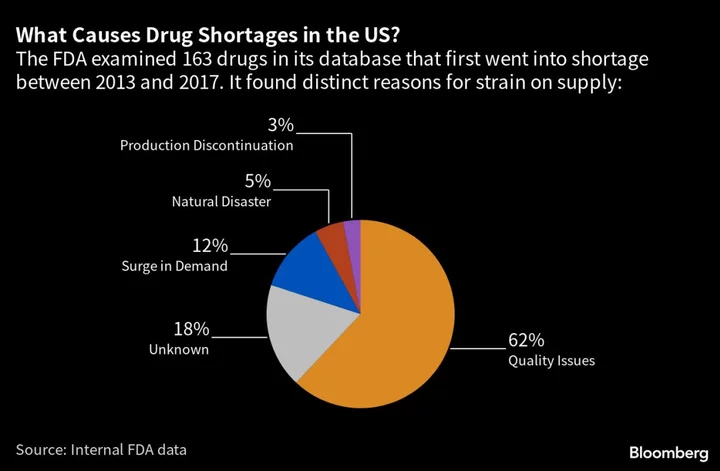

The FDA said in 2019 that 62% of drug shortages were caused by quality issues. Sometimes even the threat of a shortage can force the US to accept drugs from low-quality suppliers that, under other conditions, would have been cut off. Drug shortages are currently at a five-year high in the US and climbing.

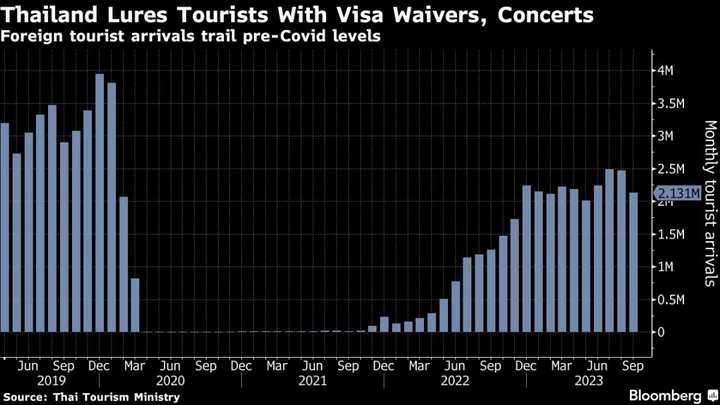

The idea for the Pentagon’s drug testing program was motivated by weaknesses in the pharmaceutical supply chain exposed by the Covid crisis. A recent Congressional mandate also required military officials to further investigate the threat of America’s increasing reliance on overseas manufacturers.

“They’re taking that risk very seriously,” said Valisure Chief Executive Officer David Light, who declined to comment specifically on the department’s plans to partner with his company.

The Defense Department didn’t comment on a detailed list of questions sent by Bloomberg News.

The Kaiser Model

The Pentagon’s proposed program follows a similar one quietly launched by Kaiser Permanente, details of which have never been reported. Kaiser, which serves 12.7 million Americans, started working with Valisure on additional drug quality checks more than two years ago, said Sean Buhler, Kaiser’s vice president of pharmacy strategic sourcing and procurement.

If Valisure detects quality issues, Kaiser turns to other manufacturers. That data also provides an early warning system for shortages: If a drug’s quality is so bad that it could trigger a recall, the health system starts preparing.

Kaiser has pursued the testing program with Valisure as “an additional assurance for our members’ safety and care beyond the current testing that the FDA is mandating,” Buhler said.

Through its testing for Kaiser, Valisure flagged that the ingredients from one supplier contained higher levels of lead when compared with another option — though both suppliers’ lead levels fell within the FDA’s standards. This finding allowed Kaiser to avoid the drug with more lead.

Kaiser isn’t the only organization trying to raise the bar on quality. Mansoor Khan, who spent 11 years at the FDA and served as director of product quality research, launched an effort in 2015 at Texas A&M University to investigate drug quality and look deeper into problems he saw while working at the agency. He sees America’s reliance on India and China as “a huge security issue.”

University of Kentucky started a program in 2019 to test drugs purchased through the college’s network of hospitals and clinics. More than 10% of drugs have been flagged with potential problems, said Robert Lodder, a pharmaceutical sciences professor who co-leads the testing effort.

These programs aim to unearth issues that are invisible to the average person. Patients may not know if they’re repeatedly taking small amounts of a chemical that can cause cancer, as has been the case with some heart and diabetes drugs.

Filling the Gap

Valisure is known for finding dangerous chemicals in drugs and personal-care products. It hopes to become the go-to source for ingredient verification for many products on store shelves.

The FDA has repeatedly pushed back against testing programs including Valisure’s, saying third-party labs don’t use the same protocols as drug manufacturers. The agency has also warned unnecessary testing and inaccurate results could exacerbate drug shortages. The FDA does a limited amount of drug testing itself.

“Protecting patients is the highest priority of the FDA,” Jeremy Kahn, an agency spokesman, said in an email. “The FDA continues to work to build a safe, secure and agile drug supply chain so that American patients have the medications they need – medications that have been carefully reviewed by the FDA for safety, effectiveness and quality.”

In response to the FDA’s suggestion that third-party labs don’t follow the same protocols as drug companies, Valisure’s Light said the company’s tests are faster and less expensive and still accurately spot problems.

A Shredding in Ahmedabad

FDA inspection documents, mainly from visits to factories in India over the past year and a half, have outlined a rash of violations. Some of the more alarming findings concern Accord Healthcare, a subsidiary of India-based Intas Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

Intas makes more than 100 generic drugs approved in the US, including copycats of the cholesterol-lowering pill Lipitor and erectile-dysfunction drug Cialis, according to an FDA database.

Last November, agency inspectors visited an Intas facility in Ahmedabad, India. Workers appeared to have recently destroyed sensitive quality-control documents, according to an account of the visit written by FDA inspectors. After shredding documents before inspectors arrived, Intas workers stuffed remnants into trash bags and tossed them into a truck, throwing acid on a bag that hadn’t made it onto the truck.

Following the inspection, Intas shut down operations at the plant. The FDA required extra testing on some cancer drugs — a slow but necessary process that resulted in shortages of critical chemotherapies like cisplatin, methotrexate and carboplatin. Last week, the FDA banned the Intas factory from sending drugs to the US. But it made an exception for 25 medications, including the cancer drugs, because of shortages. Intas didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The FDA is similarly allowing Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. to send another widely used cancer drug to the US despite it being made in a factory in India that was so rife with safety violations it was banned in December from selling an undisclosed number of other treatments in the US.

Both Sun and Intas are required to get extra quality tests on the drugs they’re sending to the US from banned factories.

A Sun spokesperson said the company is “taking all necessary steps to resolve the outstanding issues as fast as possible.”